|

|

|

|

Let's start with this passage from an old school tetbook aimed at 14-year-olds: Source ABefore 1917, Russia was very poor and underdeveloped, and in many ways was more like a country of the middle ages. The [relatively small] amount of coal and iron produced, the length of the railways and the value of exports gives a true picture of just how underdeveloped Russia was. To add to this, in Russia an average of 8 people in every 10 could neither read nor write. All power rested with the Czar, backed by a small group of powerful nobles and the church. The majority of people were treated little better than animals, with never enough food clothing or shelter. Much of the money they did earn was taken from them by the greedy landowners, who lived in magnificent luxury. The government was weak and powerless when dealing with the nobles, but savage and cruel when dealing with the workers… For a very small offence a man could be sent to prison, or to exile in the mines of Siberia where often cold and appalling conditions put an end to his sufferings. The officials – police, tax-collectors, judges – were as much tyrants as the nobles, and were usually corrupt and easily bribed. There had been a minor revolution in 1905, and as a result the Czar had been forced to allow a parliament of sorts, called a Duma, to be elected. It had little power, however, and the Czar could over-rule any measures it passed. Having at last a parliament, only to find it completely useless, made the people more bitter than ever in their hatred of the ruling class. Peter Moss, History Alive 4 (1967)

|

Consider:Analyse Source A. What is the author telling you about:

|

Ruling RussiaIf you have analysed Source A, you already have a very simplified idea of what Traditionalists Used To Say (TUTS) about Nicholas II’s Russia. Modern histories, however, have revealed a different picture of things We Only Recently Discovered (WORD), and you can reveal what they are saying by clicking the orange arrows. In what follows, quotes from school textbooks are marked with an asterisk (*); all other quotes are from academic historians.

|

Going DeeperThe following links will help you widen your knowledge: Basic accounts from BBC Bitesize Old Bitesize - on the WaybackMachine Photographs of Russia 1905-15 - huge collection

YouTube Russia in 1900 - brief overview Problems facing Russia in 1900

Old textbook account of the rule of Nicholas II |

EconomyTUTS: The economy was backward, especially agriculture, which was unable to feed the growing population, leading to famine (the harvest failure of 1891-2 claimed 400,000 lives) and poverty.

|

|

PeasantsTUTS: Three quarters of the people were impoverished peasants – “tilling an allotment of land that was barely able to produce a subsistence” – characterised by deference and backwardness; though this was presented as a strength of the monarchy, because the peasants believed in the Tsar as their God-ordained ‘father’ – they were politically inactive, and not a seedbed for proletarian revolution.

|

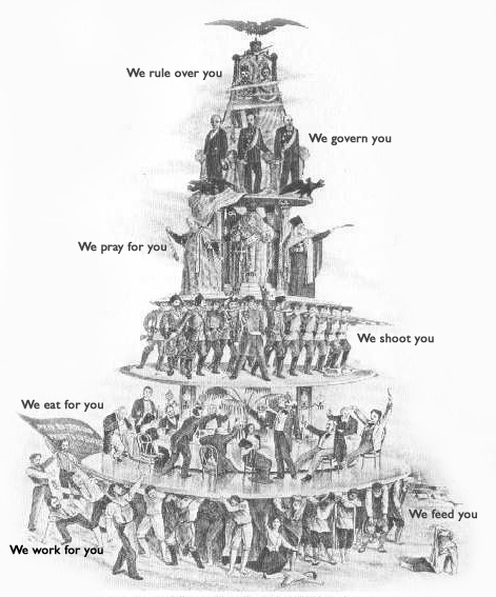

A cartoon published in Switzerland in 1900 by exiled opponents of Tsarism, showing a 'social pyramid' of imperial Russia. You can see a similar 'wedding cake' here. |

WorkersTUTS: “There was little or no labour legislation; no trade unions; no rights of combination, assembly, strike or speech. The working class, quite simply, had no rights. The working day varied between ten and fourteen hours. The textile workers in the Moscow region usually lived inside the mill itself, sleeping in the workshops. Even in the case of the best-paid workers it was rare for a family to have the use of one whole room; several families would generally be crowded together in a single room.” As a result, “socialism, communism, and anarchism progressively gained popularity in Russia”, leading to the 1917 revolution.

|

|

AristocracyTUTS: “The nobles were rich and powerful. [Just 700 nobles] owned a quarter of the land and lived a life of luxury, waited on by lots of servants”*. “The strongest supporters of the Tsar’s autocratic rule were the nobility”*.

|

|

ChurchTUTS: “Most people were members of the Russian Orthodox Church. Its priests told people it was a sin to oppose the Tsar. The Church owned a lot of land, and the head of the Church was one of the Tsar’s ministers.”* The head-quarters of the Okhrana (secret police) were in the St. Petersburg Ecclesiastical Academy, linking it with the Russian Orthodox Church.

|

|

GovernmentTUTS: The Tsar was an autocrat. “There was a Council of Ministers – but these were nobles that he chose. Opposition was illegal, and the Tsar used the Okhrana (secret police) to arrest and exile thousands of opponents”*. There were 61,000 trials for political opposition 1906-1913, with 6,000 sentenced to hard labour, 29,000 to exile, and 214 to death. Russia was huge – it took a week to cross by train. As well as 56 million Russians, it included 22 million Ukrainians, 8 million Poles (who rebelled in 1830 and 1863), and more than 100 other languages. At best this made for “a creaky structure of power”, and at worst meant “it was next to impossible to formulate policies that could be applied consistently throughout the empire … the empire was overgoverned at the centre and under-governed at local level”. Since everything had to go through the Tsar, decision-making was slow, and because ministers reported separately to the Tsar, it was uncoordinated and unchecked. “For all its immense territory and claim to great power status, the Russian Empire was a fragile, artificial structure, held together not by bonds connecting rulers and ruled, but by the bureaucracy, police and army”.

|

|

TsarTUTS: “Nicholas II, though full of good intentions, was a weak an obstinate ruler”*, “out of touch with the Russian people”*, whose father had declared him “a child, with infantile judgements”, and who found ruling boring (see Source B). The historian Bernard Pares write in 1939: “I have become quite convinced that the cause of the ruin came not all from below, but from above… The Tsar had many opportunities of putting things right ... he did not. The reign of Nicholas II had gone bankrupt of itself.”

|

Source BThe daily work of a ruler he found terribly boring. He could not listen long to minsters’ reports. He liked ministers who could tell an amusing story and not weary him with too much business. The Tsar, described by Alexander Kerensky in 1965. Do you believe this? Kerensky took over the government in the revolution of March 1917. How likely was Kerensky to say Nicholas was a fantastic ruler?

|

Consider:1. Building on your analysis of Source A, using only the' traditionalist' (TUTS) statements and information, make (a) a list of problems/weaknesses facing Nicholas II, and (b) a list of the monarchy's strengths/advantages. 2. I did that for my students in the 1990s.

3. Now go through the more up-to-date (WORD) ideas. Do they cause you to re-assess any of the 'strengths' and 'weaknesses'? Re-configure your lists taking ALL the information on this webpage into account. 4. Debate: what was the worst problem facing Nicholas II (and why)?

|

|

|

| |