|

| |

|

i 'The only war aims were self-defence and victory.' There was no ideological line-up. Britain and France, western democratic nations, were linked up with autocratic, imperial Russia. Germany, ultra-modern in its economy and highly efficient militarily, was allied to an old multi-national empire, and to Turkey, a semi-Asiatic imperial power. The longer the war went on, the more the basic aim hardened into survival or destruction as a nation state, for each of the major powers. ii The invasion of Belgium brought Britain into the war, but she fought to preserve her own national position against the threat of European domination by Germany. If France fell, British trade, sea power and national security would be in dire danger. France fought to defend her national independence and to survive as a European power. Russia's aim was to keep Austria out of the Balkans and to preserve the free passage of the Straits on which so much of her trade depended. Austria went into the war to crush Serbia, whirls she saw as a threat to her security and as an obstacle to her expansion south-eastwards. Germany claimed that her alliance with Austria was the cornerstone of her whole policy and of her position in Europe. By 1914, Germany was also vitally interested in the fate of the Turkish Empire.

B The Balance Between the Powers i The Allies had the advantage of the moral cause which Germany lost by the invasion of Belgium, and later by unrestricted submarine warfare. They also enjoyed naval superiority, of vital importance in the blockade of Germany and in keeping the Allied supply lines open. They could also attack Germany from two fronts for most of the war, though the closing of the Straits by Turkey, which cut off effective military aid from the Russians, was a severe disadvantage. ii France had the most effective army of the Entente powers, ceive them. Belgium, a flat country, was particularly suited to easy movement, and speedy advance. This was the essence of the Schlieffen Plan. iii The German attack began on August 4. Brussels, the Belgium capital, fell on August 20, and Namur, a key defence point, on August 25. The British Expeditionary Force met the Germans in The Allies faced the difficulty of longer lines of communication, since they were fighting from the outside against the AustroGerman advantageous central position. It was easier for the Central powers to strike in any chosen direction and to switch their strength from one front to another. On the Western front certainly in the earlier part of the war, the Germans had superiority of numbers and a more unified command. Communication between the French and British Commanders in the early stages of the war was unsatisfactory and the British Expeditionary Force, though one of the best trained forces of all, amounted at first to only six divisions. iv The basic German advantage lay in a very large, highly efficient army, the best in Europe. A quick knock-out blow against France was essential from the German point of view, so that German forces could then be switched to the Eastern front to strike a similar blow against Russia. When the Schlieffen Plan to crush France failed in the West, the war became a war of attrition in which neither side could strike the decisive blow.

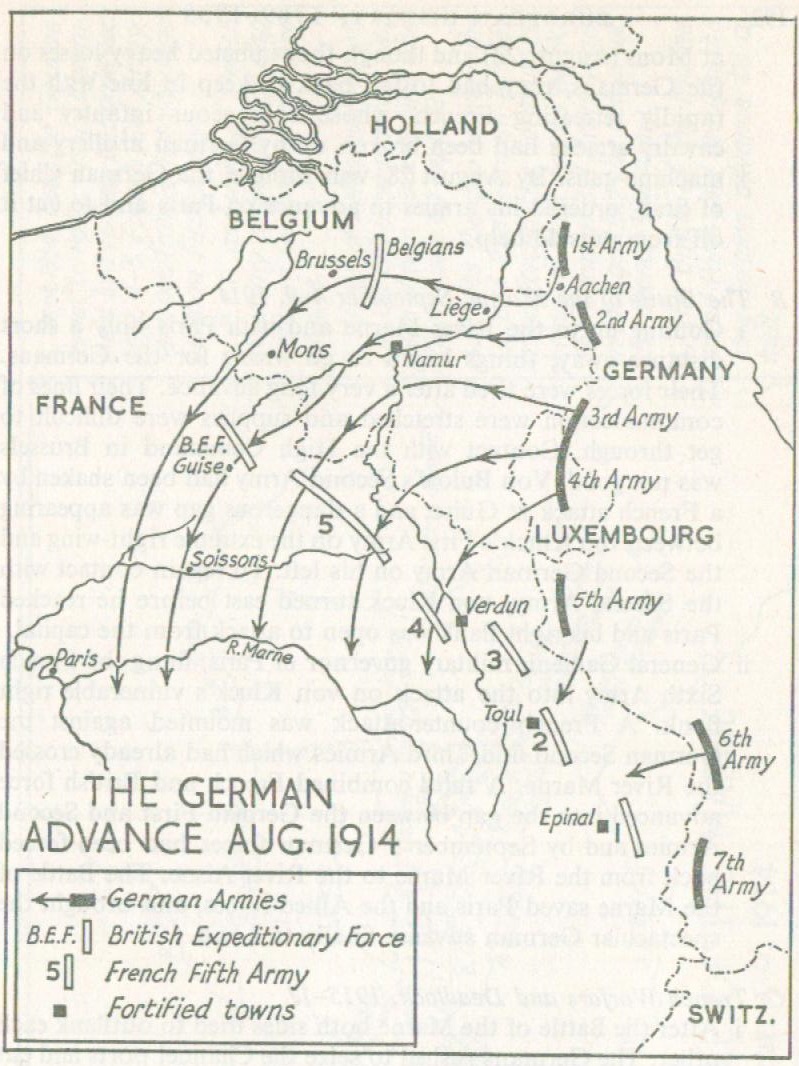

2 The War on the Western Front A The Schlieffen Plan, August-September 1914 i Eastern France was difficult to attack because of the rough and mountainous country and because of the long line of French fortifications from Mezieres to Belfort. The Germans therefore decided to concentrate four German armies on the eastern frontiers of Belgium and Luxemburg. These armies were to drive west and south through Belgium, Luxemburg and Northern France, pushing French and British forces before them. Once the right-wing German forces had encircled and cut off Paris, the whole German force would turn eastwards to crush what remained of the Allied forces, up against the German frontier where further German troops would be ready to receive them. Belgium, a flat country, was particularly suited to easy movement, and speedy advance. This was the essence of the Schlieffen Plan. ii The German attack began on August 4. Brussels, the Belgium capital, fell on August 20, and Namur, a key defence point, on August 25. The British Expeditionary Force met the Germans at Mons (August 22) and though they inflicted heavy losses on the Germans, they had to fall back to keep in line with the rapidly retreating French, whose courageous infantry and cavalry attacks had been broken up by German artillery and machine-guns. By August 28, von Moltke, the German Chief of Staff, ordered his armies to advance on Paris and to cut it off from outside help.

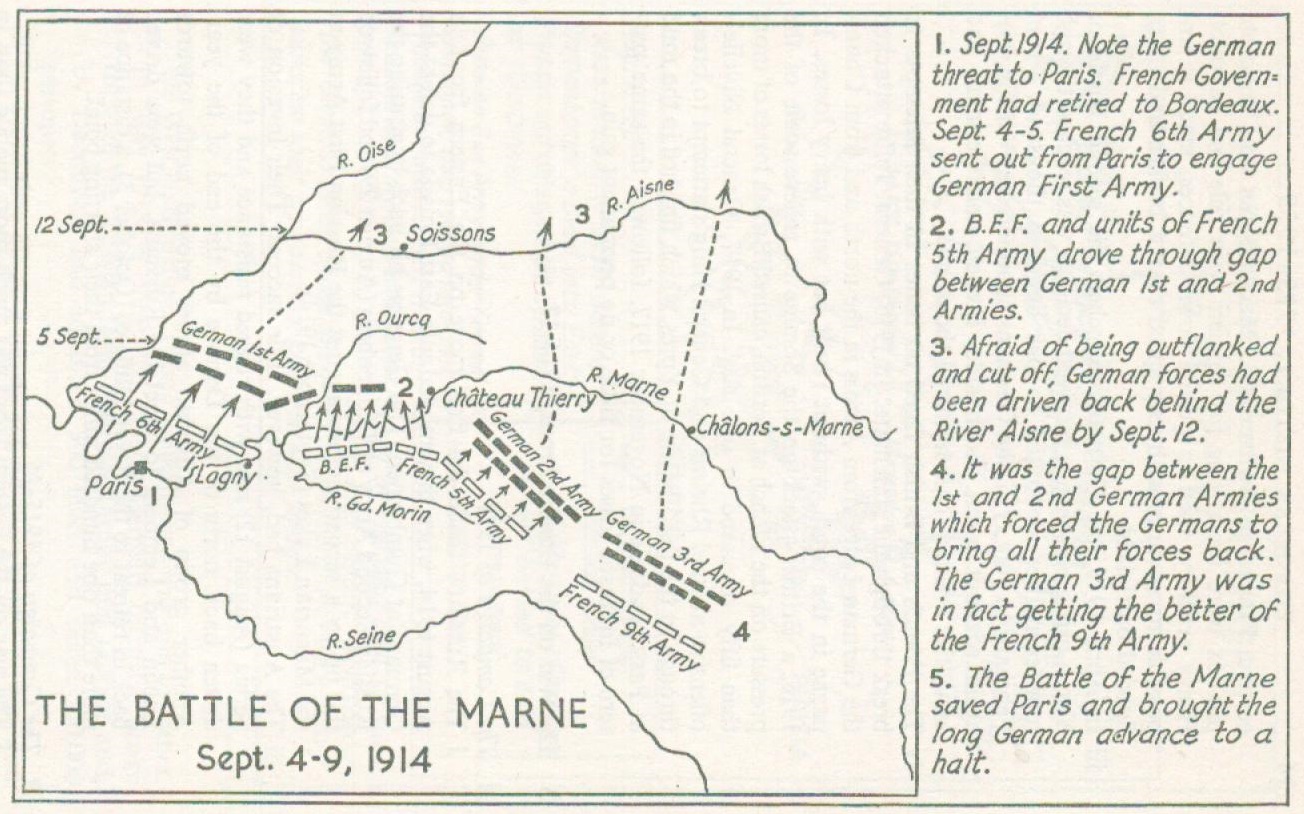

B The Battle of the Marne, September 4-9, 1914 i Coming up to the River Marne and with Paris only a short distance away, things began to go wrong for the Germans. Their forces were tired after a very long advance. Their lines of communication were stretched and supplies were difficult to get through. Contact with the High Command in Brussels was not good. Von Bulow's Second Army had been shaken by a French attack at Guise, and a dangerous gap was appearing between von Kluck's First Army on the extreme right-wing and the Second German Army on his left. To regain contact with the Second Army, von Kluck turned east before he reached Paris and his right flank was open to attack from the capital. ii General Gallieni, military governor of Paris, flung the French Sixth Army into the attack on von Kluck's vulnerable right flank. A French counter-attack was mounted against the German Second and Third Armies which had already crossed the River Marne. A third combined French and British force advanced into the gap between the German First and Second Armies and by September 9 German forces had been forced back from the River Marne to the River Aisne. The Battle of the Marne saved Paris and the Allied forces, and brought the spectacular German advance finally to a halt.

C Trench Warfare and Deadlock, 1915-17 i After the Battle of the Marne both sides tried to outflank each other. The Germans rushed to seize the Channel ports and cut off British help from France. The Allies hoped to push the Germans out of France. The lines of battle moved west and north until they reached the coast at Nieuport. The last gap through which either side could push was around Ypres, where fierce battles were fought on October 30 and November 11. id This was the end of open fighting in the West. Both sides became pinned down in lines of trenches and defence works, which stretched from the Channel coast across northern and eastern France to Switzerland. Machine-gun and concrete pill-box were too strong for soldiers with rifle and bayonet. Heavy artillery, used to pound down defences, made it impossible to advance with any speed over a broken and often flooded battlefield. iii In April 1915, the Germans launched the second Battle of Ypres, using poison gas. No vital decision was reached though total casualties amounted to one hundred thousand. From February to July 1916, the Germans hammered at Verdun, but again without result. Each side, French and German, had casualties around three hundred thousand. iv The French and British fared no better in their attempts to break through the stalemate. In 1915, General Joffre attacked the German bulge from Artois in the north and from Champagne in the south, without result but with heavy losses. In 1916, a British attack on the Somme to relieve some of the pressure on the French at Verdun, caused British losses of more than fifty thousand in one day. In 1917, General Nivelle's offensive around Rheims and General Haig's attempt to break through in the third Battle of Ypres, which finished in the mud at Passchendaele in November 1917, followed the same pattern of fantastic losses for little or no permanent gain.

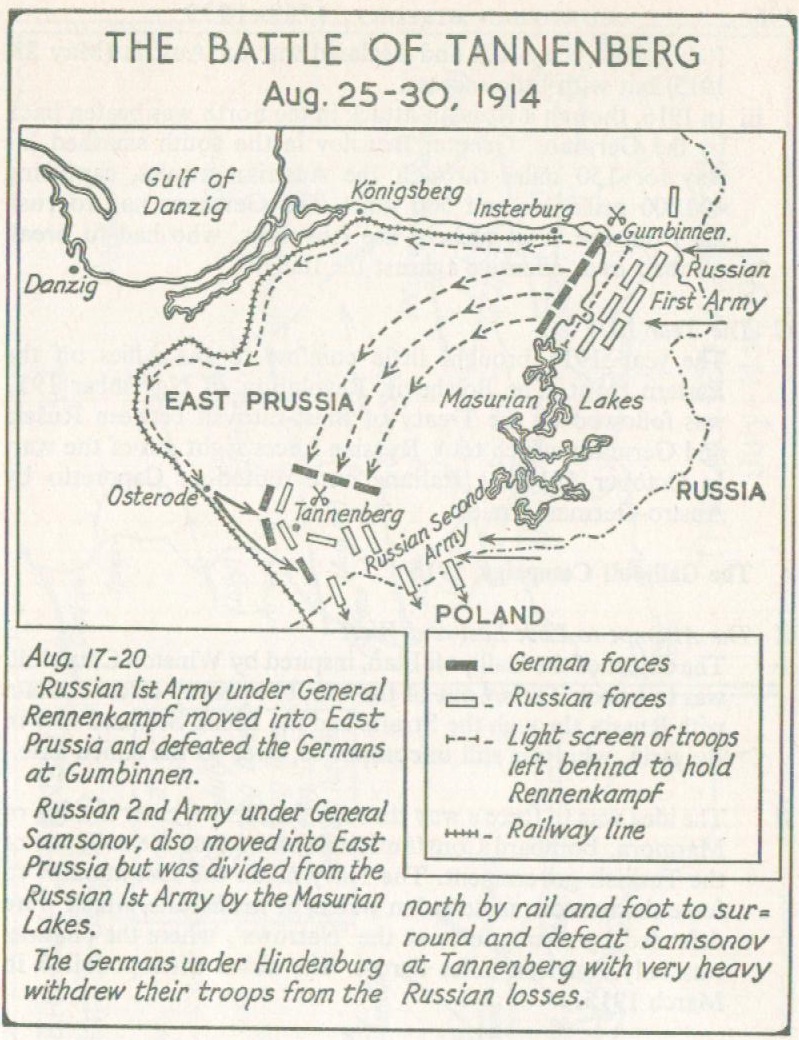

3 The War on the Eastern Front, 1914-17 i The Russians made the first move on the Eastern front in August 1914, when they moved into East Prussia to defeat the Germans at Gumbinnen. The Germans hit back by routing the Russian Second Army at Tannenberg (August 29) and followed this up by a second victory against the Russian First Army at the Masurian Lakes (September 1914). ii The Austrians had, however, little success. Their invasion of Serbia (August 12) met with rugged resistance and they were driven back north of the Danube by the end of the year. Another group of Austrian armies moved north towards Lublin and Lemberg to meet the Russians, but were driven back in retreat to the River Dunajec (October 3), a distance of more than one hundred miles from their starting point.

i The war on the Eastern front was much more mobile than in the West, and fortunes swung violently one way and the other. In May 1915, a combined Austro-German offensive broke through the Russian front between Tarnov and Gorlice and by December, had advanced 300 miles and taken 300,000 prisoners. ii In September 1915, Bulgaria joined the Central powers and Serbia, attacked by both Austria and Bulgaria, was overrun. Italy joined the Allies and declared war on Austria (May 23, 1915) but with little success. iii In 1916, though a Russian attack in the north was beaten back by the Germans, General Brusilov in the south smashed his way for 150 miles through the Austrian armies, capturing 400,000 prisoners and 500 guns. The Germans had to rush aid from the West to help the Austrians, who had to break off their own offensive against the Italians.

The year 1917 brought little comfort to the Allies on the Eastern front. The Bolshevik Revolution of November 1917 was followed by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Russia and Germany which took Russian forces right out of the war. In October 1917 the Italians were routed at Caporetto by Austro-German armies.

4 The Gallipoli Campaign, 1915 A The Attempt to Link East and West The object of the Gallipoli Plan, inspired by Winston Churchill, was to knock Turkey out of the war, to open up direct contact with Russia through the Straits and the Black Sea, and to win Bulgaria, who was still uncommitted, over to the Allied side.

The idea was to force a way through the Straits, enter the Sea of Marmora, bombard Constantinople and cause the collapse of the Turkish government. The Navy made the first attempt to force the narrow, mine-laden waters of the Straits, which were defended by strong forts at the 'Narrows', where the channel was only fourteen miles across. The naval attempt failed in March 1915.

C The Attempt on the Peninsula A second attempt was made by a combined force of British, Australian and New Zealand troops which landed on the Gallipoli peninsula to destroy the forts and clear the way for the ships to try again. Turkish troops, warned by the earlier attempt and reorganized by the German military mission under Liman von Sanders, pinned down the Allied soldiers who were withdrawn at the end of the year. It was a daring, imaginative scheme, badly carried out. Successful, it could have altered the whole trend of the war by strengthening the Allied position in the Balkans and by opening up an invaluable supply line to the Russians.

5 The End of the War - November 1918 A Moving to a Decision, 1917-18 i America entered the war on the side of the Allies in April 1917. The Germans, freed from the burdens of the Eastern front by the Bolshevik Revolution, swung all their forces on to the Western front in a major offensive in March 1918. They aimed to defeat Britain and France before help from the U.S.A. could be built up to its maximum strength. When this German attack was finally halted in the summer of 1918, the Allies were able to drive back the German troops in a retreat which ended in the armistice of November 1918. ii The Americans were drawn into the war partly because of a plan by the Germans to back a Mexican invasion of the U.S.A. in case the Americans entered the war, but more particularly because of unrestricted German submarine warfare on all shipping approaching the western shores of the Allied nations.

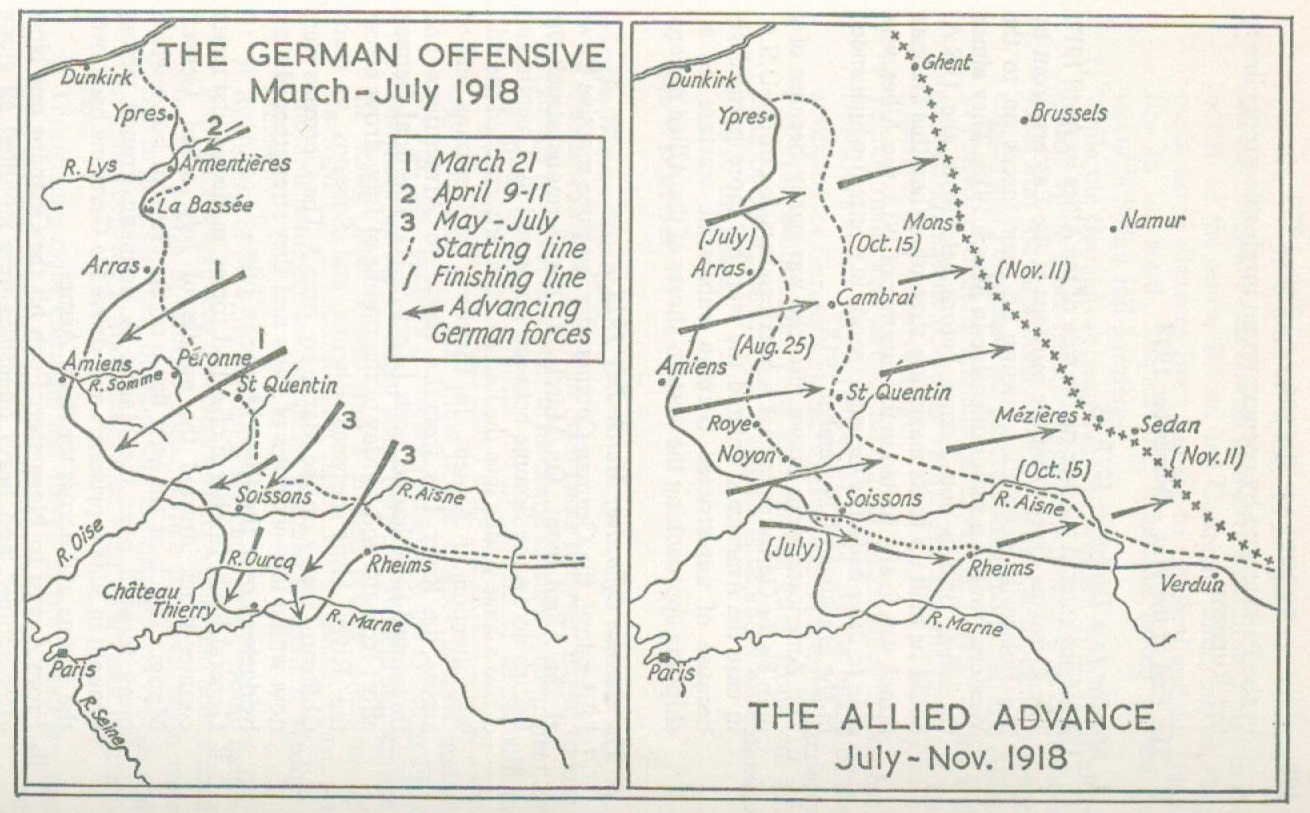

B The German Offensive, March-July 1918 i Ludendorff, the German Commander, hit three massive blows at the Allied front. On March 21, the Germans struck the British across the Somme between Arras and St. Quentin and drove a huge wedge into the line which nearly reached the railway junction of Amiens. In Flanders the Germans pushed across the River Lys from La Basse to Armentieres and threatened the Channel ports (April 9-11). The final German effort from the end of May to the middle of July, drove across the River Aisne between Rheims and Soissons to reach Chateau-Thierry on the Marne by June 3. The Germans were now within fifty-six miles of Paris and they strengthened their bridgehead over the River Marne in July. ii General Foch, in charge of Allied forces, made his first major counter-attack around the middle of July, when General Manain struck at the west flank of the German bulge which hung forward over the Marne. A dramatic French victory brought in 30,000 prisoners and drove the Germans back over the Marne and across the River Aisne. iii From August to November, Foch hit the Germans one blow after another, and heavy offensives were mounted all along the line. Belgians and British drove forward from Ypres in the north. In the centre British and Canadian forces under Haig made rapid advances from Amiens to Cambrai and St. Quentin. In the south, French and American forces moved on towards Sedan and Mezieres. iv While the Germans retreated on the Western front, their allies folded up on other fronts. Bulgaria surrendered in September 1918, and started a collapse of the whole south-eastern front. Czechs and Poles deserted the Austrians and joined the Allies. In Palestine, General Allenby captured the Turkish Army and entered Damascus (October 1918). The Italians defeated the Austrians at Vittorio-Veneto. v The Germans were already asking for an armistice in October. Hostilities ended on November 11, 1918. By the terms of the armistice the Germans agreed to evacuate all invaded territory and Alsace-Lorraine. They also moved back from the left bank of the Rhine and the bridgeheads behind it were handed over to the Allies.

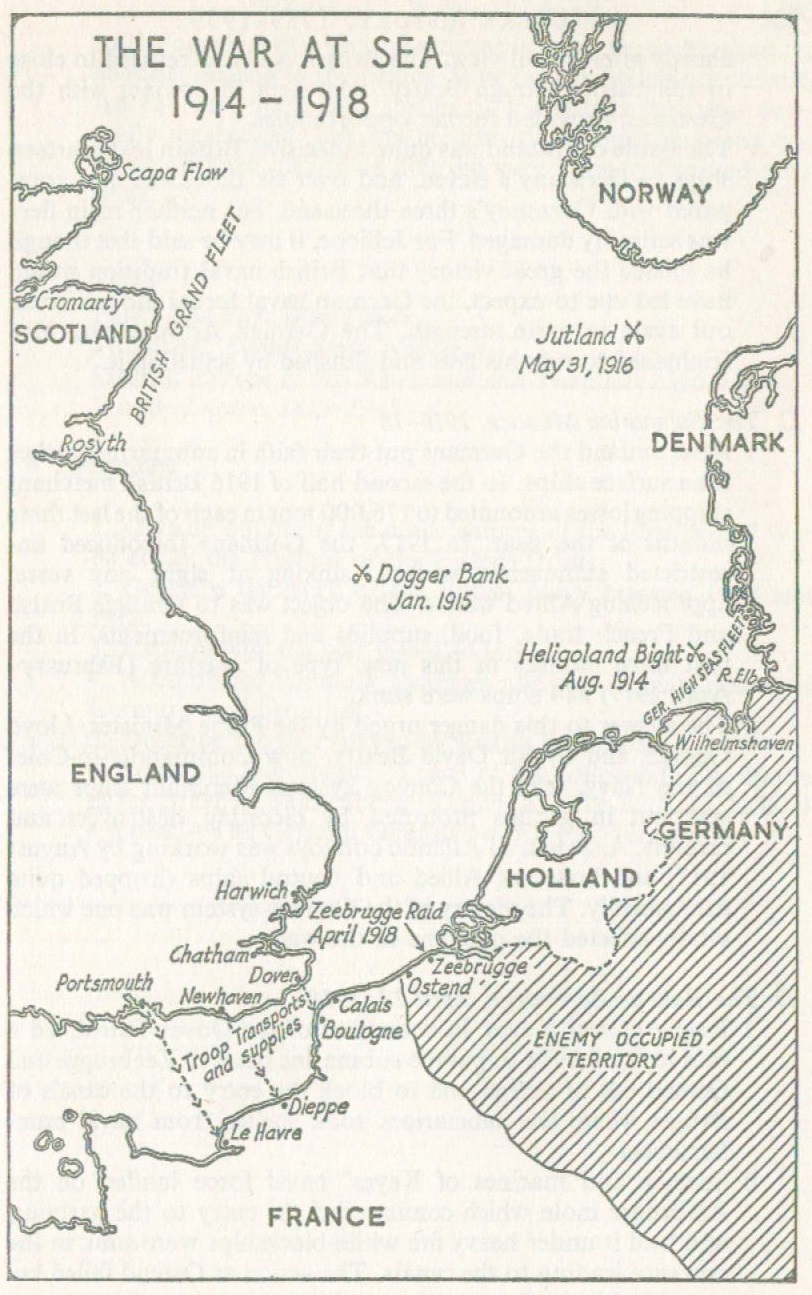

i The British Navy had four main tasks to cover. It had to keep British trade routes open, to blockade Germany, to protect the transport of Allied soldiers and to contain or better still to destroy the German High Seas Fleet. The British Grand Fleet was stationed at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands and at Rosyth, near Edinburgh, to keep an eye on the German Fleet which lay on the German coast between Wilhelmshaven and the River Elbe. There was a British cruiser squadron at Harwich and a Channel fleet based on the south coast. At Malta, a battle-cruiser squadron watched the eastern Mediterranean. ii By the end of 1914, the British Navy had swept German battleships off the high seas and German cargo ships had been forced to take refuge in neutral ports. British merchant ships were free to go about their business and the transport of troops and supplies between Britain and France went on without interruption. iii Though the main German fleet stayed in port, the Germans used a naval squadron under Graf von Spee, which had been based in the Far East as a raiding force against British ships in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Von Spec sank the British cruisers, Good Hope and Monmouth in the Battle of Coronel, off the coast of Chile (November 1914). The British Navy destroyed Von Spee's force off the Falkland Islands (December 1914) including the heavy cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The Emden, one of Von Spee's ships, escaped into the Indian Ocean where she sank several British merchant ships until the Australian cruiser Sydney caught up with her in the Cocos Islands and sank her. iv In home waters, Vice-Admiral Beatty sank three German light-cruisers and a destroyer off Heligoland Bight (August 28, 1914) and, in January 1915, a second British naval force under Beatty engaged four German battle-misers off the Dogger Bank. One German cruiser was sunk but the other three managed to escape. Beatty's flagship, the Lion, had been slowed down by German gunfire and his signals to the other British battleships to continue the chase were misunderstood.

B The Battle of Jutland, May 31, 1916 i Admiral Jellicoe, Commander of the British Grand Fleet, was extremely cautious about engaging the main German Fleet because of the new dangers to a surface fleet from mines, torpedoes and submarines. This was certainly one reason why the British Navy lost the opportunity of crippling the German naval forces at the Battle of Jutland on May 31, 1916. ii The Battle of Jutland which was fought off the Norwegian coast was the one major naval engagement of the war. Two hundred and fifty ships of war, sixty of them mounting eleven-to fifteen-inch guns, were present in the battle area. It was the last great naval battle unaffected by air power. iii The Germans planned to entice out main units of the British Fleet against a light naval force under the German Admiral Hipper, in order to draw them on to the German High Seas Fleet which was lying close behind Admiral Hipper. The British obtained full knowledge of the plan through intercepted signals, and sent out a decoy force under Beatty to engage Hipper, while the British Grand Fleet under Admiral Jellicoe followed up to engage Admiral von Scheer and the main German fleet. iv Beatty engaged Hipper and gave Jellicoe the chance to catch the main German fleet by surprise. The Germans turned away from Jellicoe's ships but by mistake they reappeared again shortly after in full view. The British Admiral refused to close in full battle, though Beatty, who kept in contact with the Germans, provided further opportunities. v The Battle of Jutland was quite indecisive. Britain lost fourteen ships to Germany's eleven, and over six thousand men compared with Germany's three thousand, but neither main fleet was seriously damaged. For Jellicoe, it may be said that though he missed the great victory that British naval tradition would have led one to expect, the German naval forces did not come out again in main strength. The German Admiral was also frightened to risk his fleet and finished by scuttling it.

C The Submarine Menace, 1916-18 i After Jutland the Germans put their faith in submarines rather than surface ships. In the second half of 1916 British merchant shipping losses amounted to 176,000 tons in each of the last three months of the year. In 1917, the Germans introduced unrestricted submarine warfare, sinking at sight any vessel approaching Allied waters. The object was to strangle British and French trade, food, supplies and reinforcements. In the first three months of this new type of warfare (February-April 1917) 844 ships were sunk. ii The answer to this danger urged by the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, and by Sir David Beatty, now Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, was the Convoy system. Merchant ships were sent out in groups protected by escorting destroyers and cruisers. A system of Atlantic convoys was working by August 1917, and losses of Allied and neutral ships dropped quite dramatically. The victory of the Convoy system was one which vitally affected the outcome of the war.

D The Raid on Zeebrugge, April 22, 1918 i Rear-Admiral Keyes, in command of the Dover Patrol, led a raid in April 1918 to put the submarine bases at Zeebrugge and Ostend out of action and to block the entry to the canals of Bruges where the submarines took shelter from naval bombardment. ii Seamen and marines of Keyes' naval force landed on the Zeebrugge mole which commanded the entry to the harbour, and held it under heavy fire while blockships were sunk in the entrance leading to the canals. The action at Ostend failed because the blockships went aground before reaching the entrance to the canals, but a second attempt in May partly blocked the channel leading to the canals. How far the raids really restricted the movement and shelter of the submarines was never really established, but the heroism of the men involved was never doubted, facing as they did very strongly fortified positions.

Questions 1. Give an outline of the main features of the First World War on either the Western or the Eastern fronts. 2. Describe the work of the British Navy between 1914 and 1918. 3. Explain why the war lasted so long. 4. Account for the early successes and the ultimate defeat of Germany and her allies. 5. Describe the part played by Russia in the war. 6. Show the importance of each of the following: The Battle of the Marne - Tannenberg - Gallipoli - The Battle of Jutland - Ypres - The German Offensive of March-July 1918. |

|

|

| |